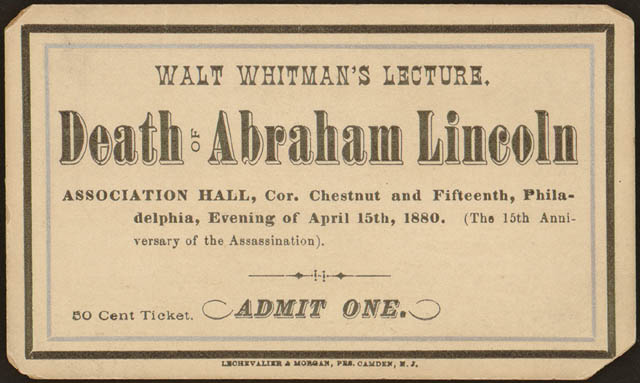

Walt Whitman's Lecture. Death of Abraham Lincoln. Philadelphia: April 15, 1880

presentation

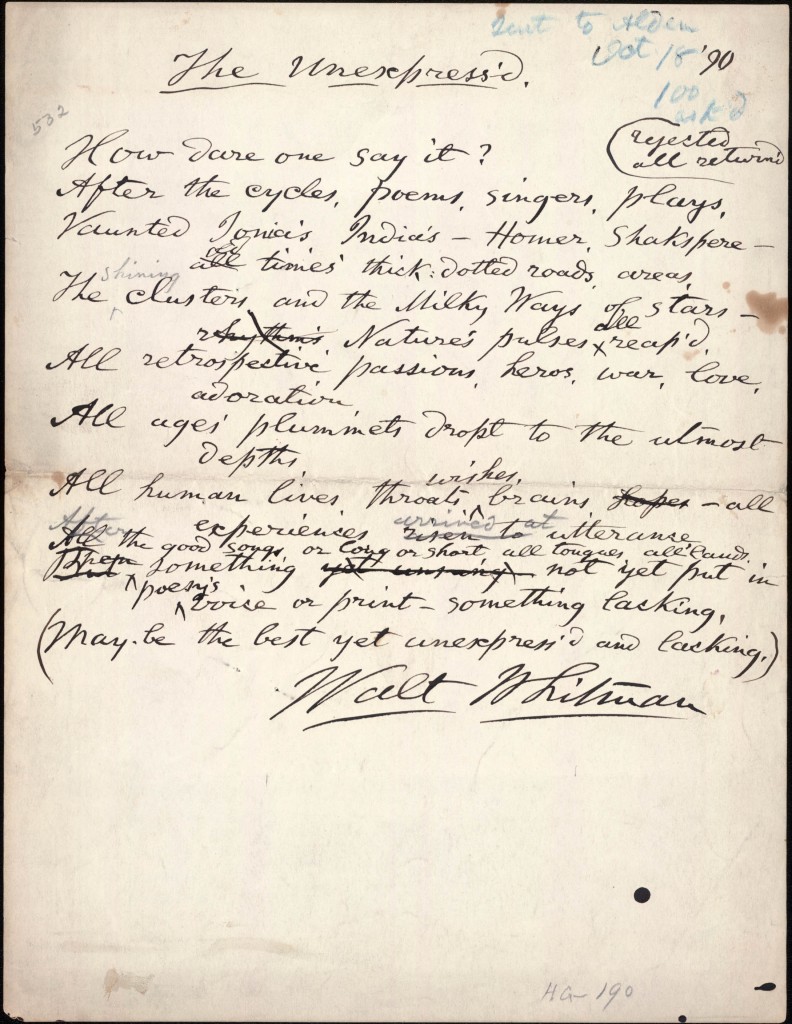

Arguably, Whitman loved his country more than almost anything else in his life. When Lincoln, who to Whitman “saved” the nation during the Civil War, was assassinated on April 14, 1865, Whitman was quick to respond. On April 16, 1865, he wrote, “…if one name, one man, must be picked out, he [Lincoln], most of all, is the conservator of it [the Union], to the future” (Whitman, Specimen Days 788). He added that even though Lincoln had died, the Union had not. This was perhaps the only solace Whitman found in the death of his hero.

While it is apparent that Lincoln was always an icon that Whitman admired, Lincoln’s importance to Whitman’s life was catapulted by the President’s assassination in 1865. Whitman viewed Lincoln’s death as akin to the many great and tragic deaths of history – Caesar, Napolean, etc… – and saw it as the final event that saved the Union and brought to a (tragic) close the chaos and turbulence of a nation (Whitman, Prose Works). Whitman conveyed these sentiments some nineteen times between the years1879 and 1890 in what became known as his “Lincoln lectures” (Reynolds 531).

While the elegiac poems are the most popularly recognized example of Whitman’s love for Lincoln today, Whitman’s annual Lincoln lectures defined his popular status in the late nineteenth century (Reynolds 496). Beginning in April of 1879, Whitman delivered these public lectures commemorating the President’s death (Eiselein 1). His first lecture, on April 14th, was organized by some of his friends in the New York literary social circle (Reynolds 531). He gave the speech seated on a chair in Steck Hall to an audience of sixty to eighty people. The entire speech was recited in a “conversational tone” and he ended the lecture by reciting “O Captain” (Reynolds 531).

The “Death of Abraham Lincoln” lecture begins with a statement of purpose:

“HOW often since that dark and dripping Saturday—that chilly April day, now fifteen years bygone—my heart has entertain’d the dream, the wish, to give of Abraham Lincoln’s death, its own special thought and memorial. Yet now the sought-for opportunity offers, I find my notes incompetent, (why, for truly profound themes, is statement so idle? why does the right phrase never offer?) and the fit tribute I dream’d of, waits unprepared as ever. My talk here indeed is less because of itself or anything in it, and nearly altogether because I feel a desire, apart from any talk, to specify the day, the martyrdom.…For my own part, I hope and desire, till my own dying day, whenever the 14th or 15th of April comes, to annually gather a few friends, and hold its tragic reminiscence…” (Whitman, Prose Works) [bold is our addition].

A tribute, to Whitman, is impossible because he cannot create one that is fitting enough. Instead, he hopes to remember the day and the importance of it. After this statement of purpose, Whitman begins with a history of the tumultuous conditions in the United States leading up to Lincoln’s election (Reynolds 441). Following this brief history lesson, Whitman reminisces about the times he saw the President. After this foundation is built, Whitman launches into his enthralling and vivid eyewitness account of Lincoln’s assassination (Eiselein 1).

“Through the general hum following the stage pause, with the change of positions, came the muffled sound of a pistol-shot…and yet a moment’s hush-somehow surely, a vague startled thrill-and then, through the ornamented, draperied, starr’d and striped space-way of the President’s box, a sudden figure, a man, raises himself with hands and feet, stands a moment on the railing, leaps below the stage…and disappears…

A moment’s hush-a scream-the cry of murder…” (Whitman, Prose Works)

Not present at Ford’s Theatre on April 14, 1865, Whitman looked elsewhere for this “eyewitness” information. Peter Doyle, a friend of Whitman’s who was at Ford’s Theatre the night of the assassination, gave Whitman an intimate account of the tragedy (Reynolds 440). Still, many of Whitman’s details were sensationalized. In his speech he included much of the sensational news reportage that was characteristic of nineteenth-century America (Reynolds 442). Many of these details, however, were only distantly related to Lincoln’s murder. Whitman concluded the detailed account of Lincoln’s assassination with commentary on the effects and meaning of the murder on the Nation. For Whitman, Lincoln’s assassination was “the ultimate violent American melodrama whose villain was a caricature of bad acting, whose victim was the hero of the nation’s greatest drama, and whose effect was audience frenzy on a massive scale” (Reynolds 443). Beyond this, though, Lincoln’s murder was the final event that re-solidified the nation. Lincoln, in his life and his death, achieved what Whitman had always hoped to with Leaves of Grass: unification of the Nation.

In this lecture, Whitman does not lament Lincoln’s death as much as he presents it as a culminating event in the midst of all the conflicts of the era. In essence, Whitman’s lecture positions Lincoln’s assassination as the tragic sacrifice through which the nation was reborn (Eiselein 1). In discussing the timeless and global impact of Lincoln’s life and death, Whitman paints an American tragedy. This tragedy was often punctuated with Whitman’s most famous tribute to Lincoln, “O Captain”.

”]

![lincoln2 Walt Whitman on Abraham Lincoln. New York: April 14, [1887]](files/2009/12/lincoln2.jpg)

The most famous of Whitman’s Lincoln lectures was his lecture on April 14, 1887 at Madison Square Theater in New York. This lecture was arranged by two businessmen who were Whitman’s friends, John Johnston and Robert Pearsall Smith. These men arranged for Major James B. Pond to publicize the event (Reynolds 558). As a result, this April 1887 appearance became a memorable spectacle and a society event. The event drew a large society crowd including Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, and James Russell Lowell. The entire “performance” had a dramatic theme, including an ending in which a young girl walked on stage to hand Whitman a bouquet of lilacs (Reynolds 555). The spectacle did not end there, however, as there was a reception following the lecture that was at least as spectacular as the event itself. Even though the event netted Whitman $600.00, he had mixed feelings about it (Reynolds 555). To John Johnston, Whitman said that this lecture was the culminating hour of his life, but to Traubel he remarked, “It was too much the New York jamboree – the cosmopolitan drunk” (Reynolds 555).

If nowhere else, Whitman’s dedication to Lincoln’s memory is evident through his final lecture. In April of 1890, despite his failing health, Whitman gave his “Death of Abraham Lincoln” lecture for the final time (Reynolds 575).

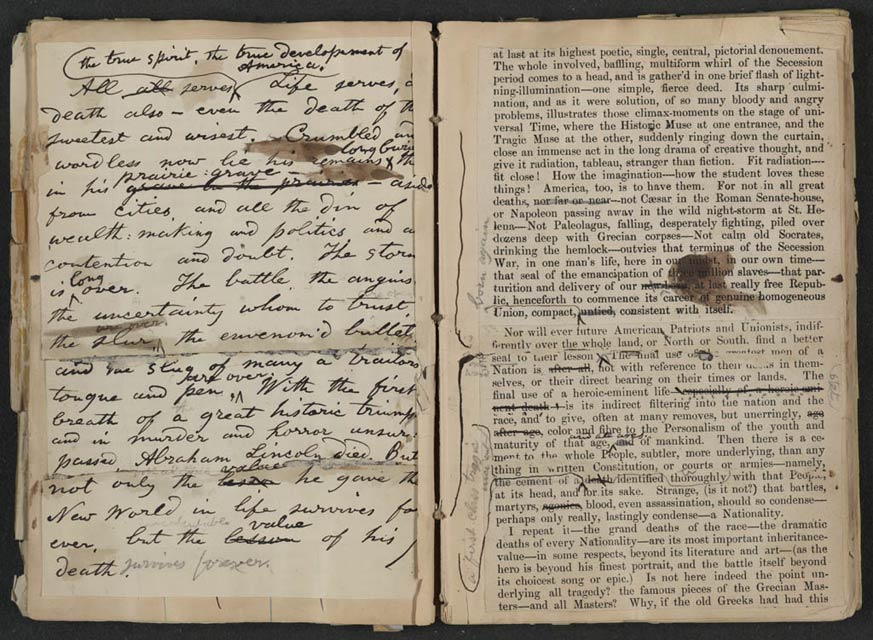

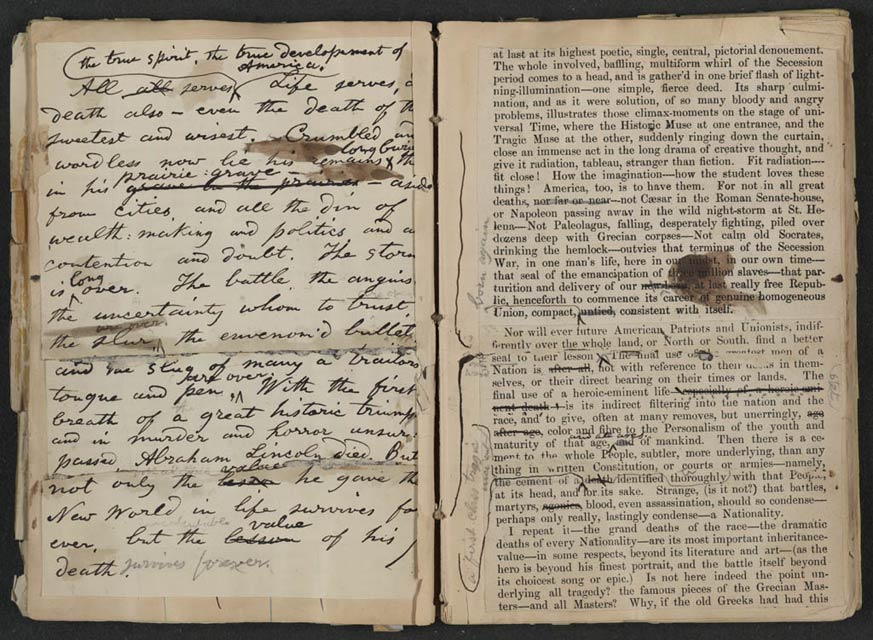

Reading copy "Death of Lincoln" lecture, 1879, Bound printed and manuscript pages

Partial Transcription: “. . .the true spirit, the true development of America. Life serves, & death also-even the death of the sweetest and wisest. . . . With the first breath of a great historic triumph and in murder and horror unsurpassed Abraham Lincoln died. But not only the value he gave the New World in life survives for ever, but the value of his death survives forever” (Library of Congress, “Poet of the Nation” http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/ww0035-trans.html).

Here’s a link to the full text of Walt Whitman’s speech, “The Death of Abraham Lincoln”.

Group members: Chris Countryman, Jennica Kwak, Tara Wood

__________________________________________

Works Cited

Eiselein, Gregory. “Lincoln’s Death.” The Walt Whitman Encyclopedia.

Eds. J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings. New York: Garland

Publishing, 1998. 30 November 2009

<http://www.whitmanarchive.org/criticism/current/encyclopedia/entry_30.html> .

Reynolds, David. Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography.

Whitman, Walt. “Death of Abraham Lincoln.” Prose Works. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1892; Bartleby.com, 2000. www.bartleby.com/229/. [30 November 2009].

Whitman, Walt. “The Death of Abraham Lincoln.” Specimen Days. Whitman

Poetry and Prose. New York: The Library of America, 1996.

All Images: Library of Congress, “Poet of the Nation: Revising Himself: Walt Whitman and Leaves of Grass.” an American Treasures exhibition: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/whitman-poetofthenation.html

Tags: Hoffman, lincoln, lincoln lectures, visitorscript, ww20

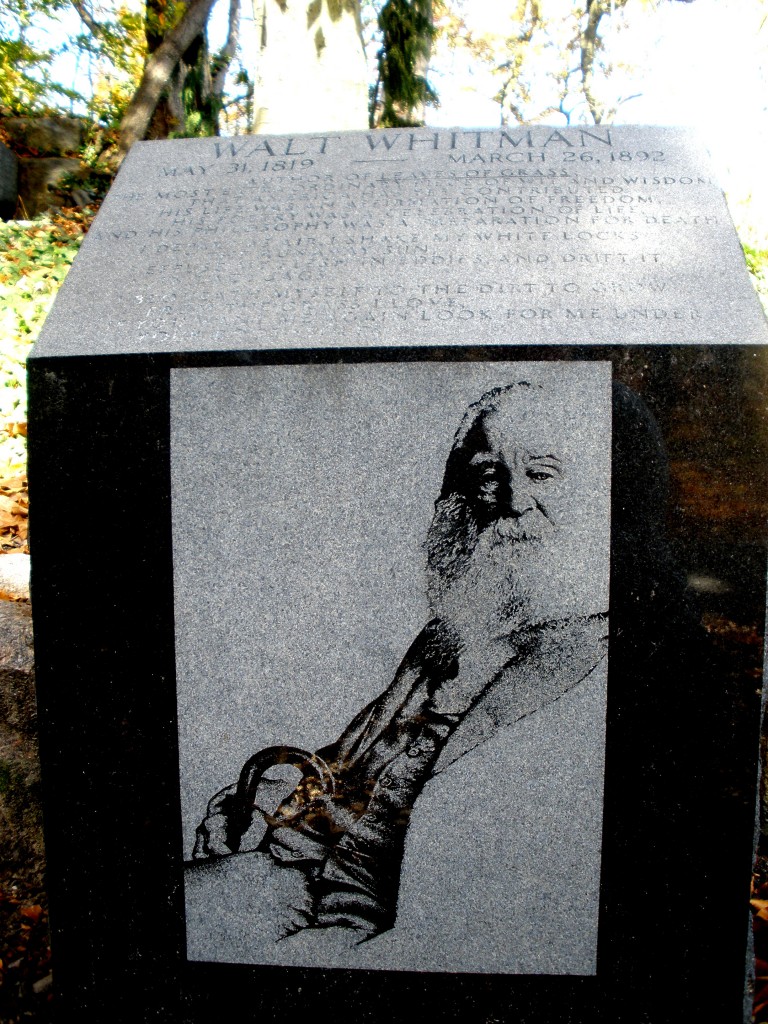

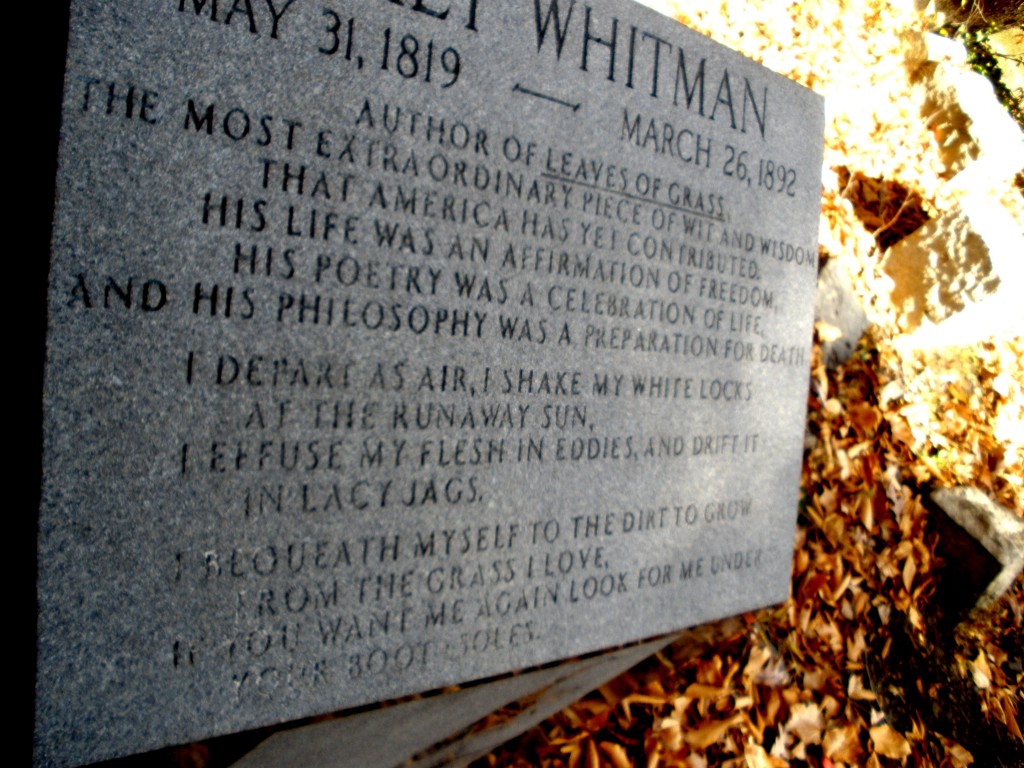

My excuse is two-fold. 1. Whitman told us (via his epitaph) to look for him under our bootsoles. I looked under my moccasins. 2. The old saying that some people come into our lives and leave footprints and we are never ever the same. I think my influence on my students is not my face – but the learning I (hopefully) inspire – about life more than English. Thus, when all is said and done, my footprints have far more impact than the rest of me – that will change, the influence will last forever.

My excuse is two-fold. 1. Whitman told us (via his epitaph) to look for him under our bootsoles. I looked under my moccasins. 2. The old saying that some people come into our lives and leave footprints and we are never ever the same. I think my influence on my students is not my face – but the learning I (hopefully) inspire – about life more than English. Thus, when all is said and done, my footprints have far more impact than the rest of me – that will change, the influence will last forever.

![lincoln2 Walt Whitman on Abraham Lincoln. New York: April 14, [1887]](files/2009/12/lincoln2.jpg)